Our two-day online PD event “When can I play I again? Guiding the Return to Sport Continuum” is coming up very soon – 19th and 20th November, 2020 (AEST time zone). One of the event’s speakers, Kellie Wilkie, gives us a sneak peek of her talk. The symposium will be ran through Zoom and spots are limited , don’t wait to register!

Low back pain is common in the general population1,2 and in sport3. Low back pain prevalence varies across different sports. Twelve month prevalence has been reported as 30-53% in rowing4,5, 78% in cricket fast bowlers6, 58-82% in cycling7,8 and as low as 1% in running9. Point prevalence has been reported as 45% in AFL10, 49% in gymnastics11 and 5.5% in basketball12. Low back pain that results in missed or modified training time can have a significant performance cost for the athlete.

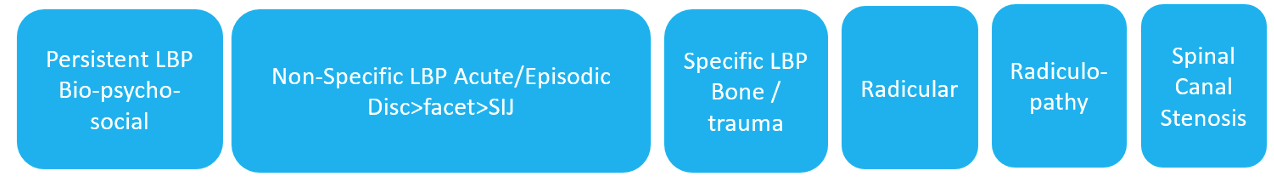

Figure 1: Low Back Pain Diagnosis

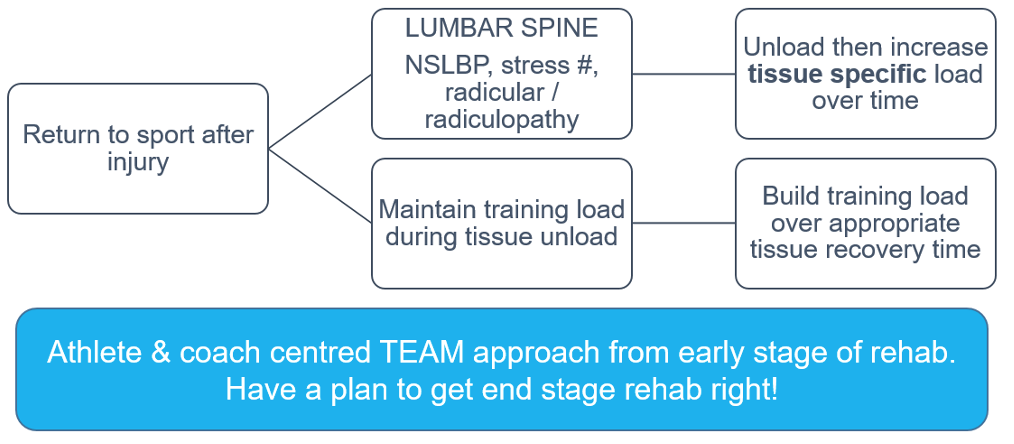

This return to sport presentation will explore how an accurate low back pain diagnosis (Figure 1) is imperative for optimal initial triage and for understanding return to sport timelines. When assessing and managing an athlete with an acute presentation of low back pain, practitioners need to be considering both the initial unload and subsequent re-load from both a tissue load and training load perspective (Figure 2). There is a lack of published evidence within the sports related low back pain literature to guide this process across all low back pain diagnosis but much can be learnt from low back pain research with the general population where comprehensive synthesis of current evidence gives us clear guidelines for the management of this condition13.

Figure 2: Increase tissue and training load over appropriate time frame.

The patho-anatomical triage of low back pain will be complemented by an exploration of the bio-psycho-social influences of an acute low back pain presentation. Athlete’s low back pain presentations are influenced by stress, anxiety, fear of movement and stressors such as imminent competition. As practitioners we need to understand that our responses to the athlete’s presentation, the reassurance and education we provide and the language that we use can help address some of the modifiable risk factors that lead to prolonged recovery.

The workshop for athletic acute low back pain will explore;

- Initial triage for accurate diagnosis

- Early aggressive unload from aggravating factors and the role of physiotherapy & medical management for control of pain

- Planning and prescribing progressions in tissue load

- Planning and prescribing progressions in training load

- Where does cognitive behavioural therapy and cognitive functional therapy fit in?

Both the seminar and workshop will emphasise the importance of establishing a culture where athletes are supported to report low back pain symptoms promptly. A multi-disciplinary approach will be advocated where all members of the medical team and coaching staff work collaboratively to ensure the athlete becomes part of the shared decision making from their initial presentation to a full return to sport.

By: KELLIE WILKIE, APA Titled Sport & Exercise Physiotherapist

REFERENCES

- Hoy D, Bain C, William G, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2012;64(6):2028-37.

- Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. The Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2356-67.

- Trompeter K, Fett D, Platen P. Prevalence of Back Pain in Sports: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sports Medicine. 2017;47(6):1183-207.

- Wilson F, Gissane C, Gormley J, Simms C. A 12-month prospective cohort study of injury in international rowers. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;44(3):207-14.

- Newlands C, Reid D, Parmar P. The prevalence, incidence and severity of low back pain among international-level rowers. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015;49(14):951-6.

- Kountouris A, Portus M, Cook J. Cricket fast bowlers without low back pain have larger quadratus lumborum asymmetry than injured bowlers. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2013;23(4):300-4.

- Schulz SS, Lenz K, Buettner-Janz K. Severe back pain in elite athletes: a cross-sectional study on 929 top athletes of Germany. European Spine Journal. 2016;25(4):1204-10.

- Clarsen B, Krosshaug T, Bahr R. Overuse Injuries in Professional Road Cyclists. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;38(12):2494-501.

- Van Der Worp MP, De Wijer A, Van Cingel R, Verbeek ALM, Nijhuis-Van Der Sanden MWG, Staal JB. The 5- or 10-km Marikenloop Run: A Prospective Study of the Etiology of Running-Related Injuries in Women. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2016;46(6):462-70.

- Hides JA, Walsh JC, Smith MMF, Mendis MD. Self-managed exercises, fitness and strength training, and multifidus muscle size in elite footballers. Journal of Athletic Training. 2017;52(7):649-55.

- Koyama K, Nakazato K, Min SK, Gushiken K, Hatakeda Y, Seo K, et al. Radiological Abnormalities and Low Back Pain in Gymnasts. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2013;34(3):218-22.

- Brumitt J, Engilis A, Isaak D, Briggs A, Mattocks A. PRESEASON JUMP AND HOP MEASURES IN MALE COLLEGIATE BASKETBALL PLAYERS: AN EPIDEMIOLOGIC REPORT. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2016;11(6):954-61.

- Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. The Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2368-2383.